Accelerate Late, Like Jannik Sinner

Velocity is a measure of speed and direction. The sentence “my racket was moving fast when I struck the ball” is referencing the racket’s high velocity.

Acceleration, on the other hand, is a measure of rate of change of velocity. Not how fast or how slow is an object’s motion, but rather, is the object’s motion getting faster or slower?

The key to an explosive forehand is not merely to swing with high velocity, but rather it is to accelerate throughout the entire swing. Even in the final few milliseconds before contact, the racket should still be accelerating. Not only is it moving fast, but it is also getting faster and faster up until the moment of contact. That is late acceleration.

The Alternative to Late Acceleration

Many tennis players fail to accelerate late on the forehand. As a result, they have long, constant speed, slow swings.

Often, this player prepares well, drives off their legs well, is on balance when they swing, and, generally, looks pretty good as they strike the ball. It’s just that… the shot isn’t fast.

There’s a missing link late in their kinetic chain, and that missing link causes the player to only accelerate early, but not late. In the moments before contact, no acceleration is occurring, and the racket is moving at a constant speed.

Players who accelerate sufficiently late, on the other hand, produce swings which continue increasing in velocity until contact. We’ll be using Jannik Sinner’s world class forehand as an example of exceptional late acceleration.

The Timing of Elite Forehands

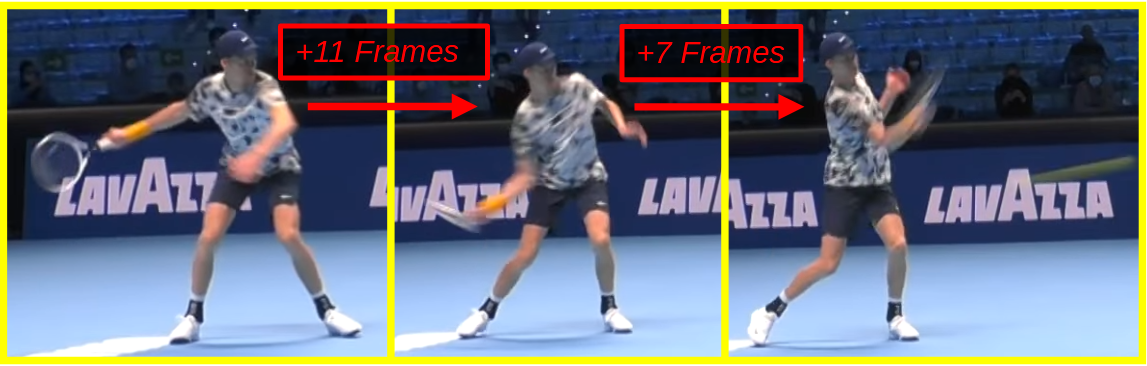

The image below is screencapped from a practice session between Jannik Sinner and Novak Djokovic, at the 2021 ATP Finals. I encourage you to watch it, as it provides a unique angle we don’t often see, an angle that’s crucial to understanding what’s really happening on a well struck forehand.

We’re discussing Jannik Sinner’s forehand today, but, if you watch the clip, you’ll see Novak implementing all of the same ideas.

The initial phase of Jannik Sinner’s forward swing is much slower than the final, explosive drive through contact. This is because, during the initial phase, the racket starts essentially at rest, and so, even when accelerated, its velocity is still close to zero. Acceleration is a rate of change of velocity over time, and therefore the longer a player can accelerate for, the higher their racket velocity will climb.

Jannik’s initial acceleration occurs as he transfers his weight forward and begins rotating into the shot. His hips and torso have begun to unwind, but because the racket started at rest, the racket’s velocity is still quite low, but acceleration has begun.

This initial move takes 11 frames.

Explosive Acceleration Through Contact

The contact phase occurs much quicker than the pre-contact phase. From the time Jannik’s elbow has just passed his hip, to the time his forward swing is completed, only 7 more frames have passed.

Not only is the contact phase shorter in duration than pre-contact, but the hand is actually covering far more distance during it. If the swing were performed at a constant speed, more time would be spent in the far greater distance contact phase than in the far shorter distance pre-contact phase. With Jannik Sinner’s elite stroke, we see the exact opposite.

Jannik’s swing is not performed at a constant speed.

This velocity increase is due to continuing acceleration. Jannik’s swing is not performed at a constant speed, but instead continues to increase in velocity all the way through contact.

The result is that the racket is moving faster and faster as the swing progresses. That’s why the early part of the swing, despite being shorter in distance, takes significantly longer than the contact phase – 157% as long, to be exact.

How do I implement this?

If you already possess an extremely explosive forehand, you’ve felt this timing discrepancy hundreds of times. Of course the early part of the swing takes longer than the contact part. All the speed comes at the end. For many players, though, this late acceleration is a mystery.

Louis Cayer, the LTA’s Senior Performance Advisor, advises players to imagine that, “the swing starts at contact.” Strange, right? How could we start the swing at contact – don’t we need to swing well in advance of contact to generate speed?

Literally, yes, but in practice, this cue is actually quite good. It’s helped many of my students break out of their constant speed swings, and harness their own late acceleration.

“Start at contact.“

Louis Cayer, LTA Senior Performance Advisor

It works because the most critical links in the kinetic chain are the final ones. The earlier links are important, but mostly discretionary. You can accelerate early by driving off your back leg, and if you have time to set up, you certainly should, but it’s not fundamental to every stroke you’ll produce. Late acceleration, on the other hand, is. You will always accelerate late on a a topspin swing, no matter what the situation, no matter how out of position you are, or how awkward the shot is.

The Early Swing = Pseudo-Preparation

Watching some players, it feels like they believe they need to create 5000 rpms of immediate, swing starting hip drive to get anything on their stroke. This is not the case.

In fact, it really doesn’t matter how hard you drive through your hips if you can’t synchronize that initial rotation with your final drive through contact. Late acceleration is so important that the beginning of your forward swing should be performed in service to late acceleration.

Here’s how you implement this:

You’re in your final preparation slot, ready to swing. As you initiate, you have a specific manner in which you want to strike the ball. An intention for the contact you’re trying to create.

The beginning of your forward swing should be performed in service to late acceleration.

The initial part of your forward swing is performed in order to allow you to accelerate late through your desired contact. The early swing rotates your body and adjusts your balance, with the purpose of, yes, generating velocity, but mostly of preparing you for your final, explosive strike through the ball. The early swing gets you into position such that you can accelerate through the strike that you visualized at swing initiation.

Hip Drive and Late Acceleration

The real magic of hip drive is that it allows for early acceleration while also preparing you for late acceleration. During preparation, you turn your hips away from your target, so that you can turn them back towards the target during the forward swing.

And if you won’t have time to re-square your hips by contact, you typically won’t turn them away during preparation. Late acceleration is the primary engine of the stroke, and early acceleration is a secondary goal that you attempt with sufficient time to prepare (which you will, on most shots). Preparation, like the early swing, exists in service to late acceleration, so if you’re too pressed for time to unwind your hips as you swing, don’t wind them up in the first place.

Preparation, like the early swing, exists in service to late acceleration.

On most shots, you will have time to rotate, and you can inject extra acceleration with your hips without sacrificing fault tolerance. Because the racket starts at rest, this initial acceleration won’t feel like much – your brain is perceiving your racket’s velocity, which is still close to zero, even though its acceleration, which you created with your rotation, is now positive.

The initial velocity your hips create stays with you deep into the motion. As long this early acceleration was performed in service to late acceleration, and you continue to accelerate all the way through contact, your combination of initial hip drive + late acceleration will result in a higher final velocity than just late acceleration would have. Early acceleration is a common way we inject effortful power into an already efficient effortless stroke.

What should it actually feel like?

This last few milliseconds before contact constitute a compact, explosive, forward flick of the arm, by which the racket is flung forward. The motion is very similar to the one used to throw a baseball sidearm or submarine style. This forward fling starts at, or just in front of, the hip, and ends after contact. During it, the racket is far from the body, with sufficient space between the elbow and the chest, so as to allow the elbow to pass through the plane of the chest unimpeded.

This critical, final injection of velocity comes late in the swing process, only fractions of a second before contact. The force is applied quickly, almost all at once, not gradually and uniformly over the entire course of a long, looping forward swing.

If you’re doing it right, you’ll be able to feel the explosive nature of the swing. It’ll be clear that the racket is moving its fastest, right before contact.

Many players attempt this final injection of pace too early in their swing process, with their elbow still stuck behind their hips, and/or with their hips not yet unwound towards their target. This ruins the efficiency of the swing, and can even cause hand, wrist, and elbow pain. It is only out in front of the chest, away from the trunk, that the shoulder/arm/elbow/forearm/hand apparatus can freely and easily perform the flicking action necessary for late acceleration.

Grip Relaxation as a Guide

We hold the racket loosely on the forehand, because if we hold it tightly, no matter how explosively we move, the racket won’t be able to whip through the air.

Try the experiment yourself (with anything long and stiff, doesn’t have to be a racket):

Hold your chosen item tightly, and swing it. Now hold it loosely, and swing it. You’ll notice a clear increase in the speed of the object when holding it loosely.

Your ability to maintain grip relaxation while accelerating functions as a good barometer for whether or not you’re successfully accelerating late. If you’re firing your final acceleration too early, it’s impossible to drive the racket with a loose grip – with your elbow stuck behind your hips, you must grip the racket tightly to get it going anywhere.

If it feels like the racket will fly out of your hand at a 3/10 grip tension, you need to wait longer in your motion before initiating your final drive through contact, whereas if you’re able to comfortably and confidently whip it through, you’re doing it right.

Comments

Post a Comment